All of us yearn for something. By this I mean a deep feeling of wistful desire, or longing, for myriad objects and aspirations as diverse as our own life experiences — a lost child, belonging, the inner peace that comes from solitude. Can landscape embody, or at least metaphorically represent these desires and mirror our internal journey? How does, exactly, “who we are” impact “how we see the land”? And what, if any, part does genetic memory — the past experiences of our ancestors, and their relationship to the land — play in how we relate to the countryside?

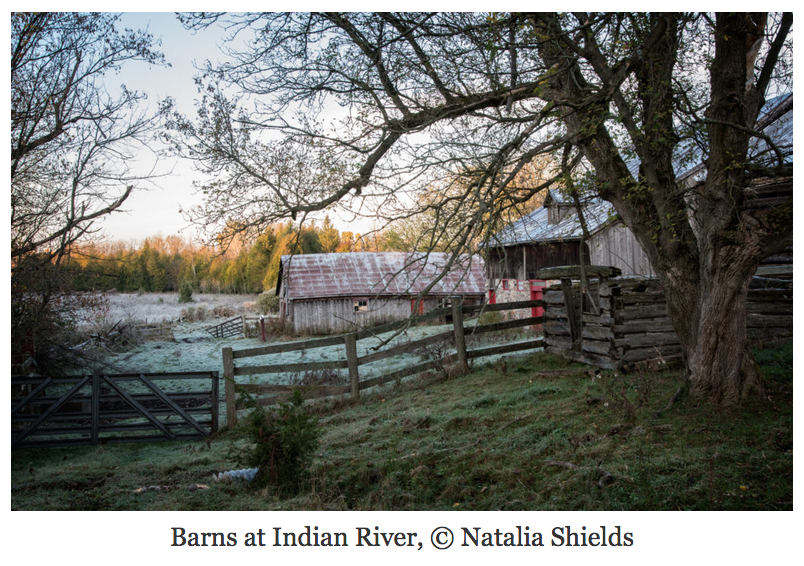

Travelling north to the Canadian Shield and cottage country, we so rarely give the bucolic and beguiling farmland above the lower Great Lakes a second glance. Yet archaeological sites reveal a rich Indigenous presence, decrepit barns — cathedral like — display noble form and function, and ancient groves echo with the sound of draft horses pulling heavy timber. Peel back the faded paint, dust off these lovely castaway relics, and you will discover them imbued with a peculiar kind of luminosity — the half-life of cultural memory.

It certainly is no secret that the rural landscapes of Southern Ontario are in transition. The decades-long downward spiral of the economic viability of the family farm has flat-lined, with farms being replaced in many cases with corporate, single crop agricultural practices. Farmland in the Golden Horseshoe is under constant threat of being gobbled up — witness the almost-50-year battle over the Pickering Airport Lands, or more recently, the Megaquarry in Melancthon. There is a devastating environmental price to be paid for all of that, but alongside this story is another more encouraging trend. A new crop of people are rediscovering the land, and, often in partnership with their die-hard neighbours with generations of farming experience, are producing gorgeous organic and naturally raised food.

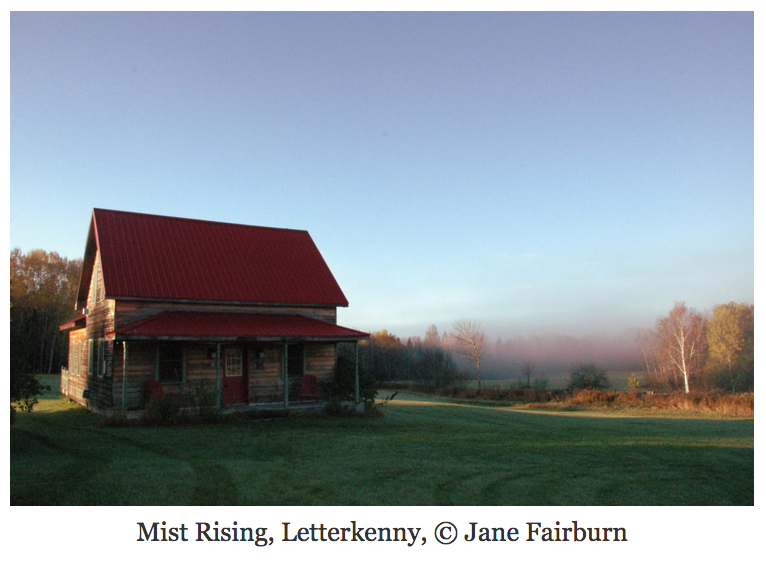

My new project, Moorlands: An Ancestral Memoir of Loss and Belonging, explores some of these ideas. The project will undoubtedly be enriched greatly by the participation of the marvelous Natalia Shields, whose photography also appears in Along the Shore. Natalia and I made a great start on the photography in the late fall of 2017, travelling back in time to the Ottawa Valley. I look forward to joining her in Prince Edward County this spring.

My new project, Moorlands: An Ancestral Memoir of Loss and Belonging, explores some of these ideas. The project will undoubtedly be enriched greatly by the participation of the marvelous Natalia Shields, whose photography also appears in Along the Shore. Natalia and I made a great start on the photography in the late fall of 2017, travelling back in time to the Ottawa Valley. I look forward to joining her in Prince Edward County this spring.

The project also has an autobiographical component. With unabashed Irish roots on both sides of the family, farming, and love of the land is in my blood. Our family spent years loving and propping up a 450 acre pioneer homestead near Eganville, in the storied Ottawa Valley. Now, the prospect of organic farming looms in Indian River, near Peterborough, but first we need a barn that’s not falling into the earth (literally)…

Thought you might enjoy this clip taken a few months ago, with two of the best stonemasons in the business, the indefatigable Ed Moseanko and Wayne Nicolas. Listen while they patiently explain the restoration process for the barn’s stone foundation, and in the process, discover an open, stone-lined well.

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Hi Jane,

It was lovely to catch up with you today again in “the old country”, ten years after meeting you in your beloved and beautiful rural Ontario.

I agree with you (and I can only speak personally) that landscape can represent and embody our earthly desires and yearnings but that it is also a channel connecting us with things ethereal.

Every time I visit the area in rural Ireland where I grew up, and where my family have lived and farmed for at least five generations, the mountains, fields and forests gently whisper to my heart that I’m home again. To me, that home is more about love and family and connectedness to my ancestors than it is about “owning” land or property. How can we “own” land that was here long before we were?

The sweet sorrow, of course, is having to be away from that land, as modern urban dwellers and migrants or indeed the “white martyrdom” or self-imposed exile of St Colmcille.

Dust we are…

Hello Cathal.

Dust we are. Indeed. And perhaps it’s that simple truth that binds us most firmly to the land. Perhaps we are drawn to the constancy it seemingly offers. The secrets it holds. The beauty it represents as a pathway to the divine.

However we see it in our mind’s eye, I think we suffer when we lose connection with the land. Leaving it, yes, as a martyr. But returning, always, as a pilgrim.