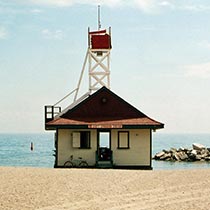

The Lakeshore

For Torontonians “the Lakeshore” is a name with layered meanings. To many people it may simply mean the water’s edge, sometimes visible, oftentimes not, that is the southern boundary of our metropolis. But “the Lakeshore” can also mean the gritty highway skirting the edge of the Lake, known as Lake Shore Boulevard. Then again “the Lakeshore,” while being a lakefront and a highway, can also be taken to mean a string of former villages and towns that still stretch along the highway for almost six miles beyond the Humber River, from the forgotten district of Humber Bay, on to Mimico, New Toronto, and finally Long Branch, on the east side of Etobicoke Creek.

What follows is the story of Gus Ryder, an exceptional Canadian, who lived and worked in the Lakeshore, founded the Lakeshore Swimming Club in 1930, and coached many swimming champions of international renown, including Cliff Lumsdon and Marilyn Bell.

Gus Ryder came by his uncanny ability to teach swimming and lifesaving honestly. Ron McAllister’s Swim to Glory indicates that some years before moving to the Lakeshore, Ryder, himself an excellent athlete, pulled a skater from the icy water of Grenadier Pond in High Park. From that time on, Ryder vowed to learn and master the art of lifesaving and become an accomplished swimmer.

Although Ryder never had children of his own, in a sense he had thousands of them, teaching the sport of swimming to countless Lakeshore children of all ages and abilities. In the summer months he ran an instructional swimming programme under the sponsorship of the Red Cross for local kids at the “Sunnyside tank”, now known as the Sunnyside – Gus Ryder Outdoor Pool. Lakeshore kids travelled back and forth to the pool using the free streetcar service for children that was provided by the Toronto Transportation Commission on many of its routes, including the Lakeshore.

Until 1952 the Lakeshore Swimming Club was without its own indoor pool. Before this, its athletes swam, in the summer months, out in the Lake: in the early years from the bottom of Seventh Street, and near the mouth of Etobicoke Creek, and later, near the mouth of the Credit River.

Ryder’s rise to pre-eminence as a swimming coach coincided with Toronto’s rising profile as the premier place in North America for marathon swimming. That story began when Toronto teenager George Young rode down to California on a battered motorcycle and was the surprise winner of the first marathon swim across California’s Catalina Strait in 1926. The trophy, donated by Arthur Wrigley Jr., named Young the Champion of the World for his twenty-mile crossing. For years after that, highly competitive marathon swimming competitions were held in Lake Ontario, in front of the Canadian National Exhibition, with a cast of local and international athletes.

As Bill Leveridge writes in Fair Sport: A History of Sports at the Canadian National Exhibition Since 1879, the Wrigley Trophy that Young won for crossing the Strait moved to Toronto the following year. On August, 31, 1927, the first “Big Swim” for the Championship of the World was held at the Canadian National Exhibition, with Ernst Vierkoetter, “the Black Shark of Germany,” taking first place in the twenty-one mile course.

During this first marathon swim, Gus Ryder saved two men who were floundering in the frigid water along the breakwater. To ward off the cold, both swimmers had covered their bodies in graphite grease, which was now threatening to suffocate them.

The Wrigley Swims lasted until 1937, with many of Gus Ryder’s athletes from the Lakeshore Swimming Club participating in its later years.

Ryder’s first swimming star was long-time Seventh Street resident and community volunteer Lucille (Lou) (née Wylie) Gamble. Though she achieved much success throughout her competitive swimming career, her prized possession was the Mayor Jackson Trophy, which she earned by winning the mile race at the New Toronto waterfront three times in a row. From Coach Ryder, Gamble not only learned to swim, but also, as her daughter Wendy Gamble has said, “the watchwords of her life: personal commitment, community service, and dedication to her sport.”

Ryder devoted as much time to teaching disabled children to swim as to coaching his star athletes. And he made sure that all of his swimmers participated in teaching these children, too. Many, including Lou Gamble, who volunteered alongside Ryder for decades and took up his work after his death, made community service their life’s work, both in the Lakeshore and farther afield.

Another Lakeshore swimmer who made a tremendous impact on the district’s community life was local hero Cliff Lumsdon, who won his first World Marathon Swimming Championship at the Exhibition in 1949, a feat that earned him the Lou Marsh Trophy for best Canadian athlete of that year. He would be awarded five individual world championships at the Exhibition in all, and would cross the Juan de Fuca Strait, between British Columbia and Washington State, in 1956.

Stated in the Toronto Daily Star to be, “one of the epic swims of the century”, Lumsdon’s effort in the 1955 World Championship at the Exhibition is perhaps his most legendary performance. In lieu of an earlier planned Lake crossing, the swim involved a thirty-two-mile triangular shaped course, in front of the Exhibition grounds. At the outset of the race, which began about one o’clock a.m. on September 9, the water temperature was reported to be close to fifty degrees Fahrenheit, a dangerously low swimming temperature.

By daylight, all but three of the field of internationally known marathoners were out of the Lake. Before the halfway point, the only swimmer left in the punishing water was Lumsdon. By mile fifteen he was suffering from terrible groin cramps and he was dragging his legs behind him, but as thousands of Torontonians began to gather on the Lakeshore, he somehow was able to summon the courage to plow forward, with Coach Gus Ryder at his side in the guide boat.

At the finish, Lumsdon, semi-conscious, was unable to pull himself up onto the barge. As he was removed from the platform on a stretcher, Gus Ryder collapsed, no doubt due to the strain of watching one of his star athletes endure such a test. The rigorous training regime Lumsdon followed in Lake Ontario undoubtedly contributed to his almost superhuman ability to remain in water that cold for so long.

A lifetime resident of the Lakeshore, Lumsdon was made a member of the Order of Canada in 1982, seven years after Coach Gus Ryder had received the same honour. Before his early death in 1991, he accompanied his daughter Kim Lumsdon, also a top marathon swimmer, during her crossing of Lake Ontario in 1976.

The first crossing of our great inland sea came more than two decades earlier, when in 1954, the Lakeshore Swimming Club’s Marilyn Bell, the spritely, otherwise average Toronto teenager, took on Lake Ontario and won . . .