The Island

Each of the sections of Along the Shore ― the Scarborough Bluffs, the Beach, the Island, and the Lakeshore ― begins with a chapter entitled “The Nature of the Place.” This chapter contains my thoughts and observations about the innermost character of each of the waterfront districts featured in the manuscript. Here is the opening to the Island chapter “The Nature of the Place.”

Torontonians are very lucky. Whenever the crush of humanity becomes too intense, whenever the pressures of Bay Street become too overwhelming, whenever the demands of urban living become too exhausting, the possibility remains of leaving all of that behind. On any given day in the downtown core, you can walk south, through the noise, the traffic and the congestion, board a ferry at the waters edge, and cross a little stretch of water to the faraway world of Toronto Island.

The Island is the alter ego to the skyscrapers of concrete and glass that stand shoulder to shoulder along the edge of the harbour, and is more accurately described as a series of “islands,” or sandbars, that form the southern perimeter of Toronto’s Inner Harbour. Collectively they constitute a place that is in equal parts captivating and unique, silent and dishevelled, romantic and isolated, a place seemingly disconnected from the metropolis yet nevertheless deeply entwined with our cultural identity as Torontonians.

Perhaps it is the very nature of the place, its wide-open spaces and its solitude, that invites us to reflection, self-examination, and introspection, for it is in the quiet corners of the Island that we can begin to ask the difficult questions about who and why and what we are, both as a city and a people. If we are patient, we may find that at least part of the answer is revealed not in the commercial towers of the financial district, nor in the elegance of Rosedale, nor even in the raucous exchanges on Yonge Street, but a mile offshore on a sliver of willow and sand, our Island, that Bohemian oasis of mystical imagination, overlooking the empire.

The allure of the Island is heightened by the fact that it is mostly hidden from the mainland by the rampant growth of waterfront towers and condominiums that occurred in the late twentieth century. Now, in the present century, Torontonians are often afforded their best views of the Island from above the city centre, whether it be from our cars on the Gardner Expressway, as we peer between the massive buildings that hug the shore, or from the highest reaches of glitzy downtown office towers. In any case it is from above that one is most struck by the size of the Island. Helped along by massive infilling projects that occurred primarily in the twentieth century, it is today more than eight hundred acres in overall area, seemingly only a stone’s throw from the city centre.

Most people, when they consider “going over to the Island,” will think of a day’s excursion on a weekend in summer, when crowds wait to bustle aboard the crowded ferries, lugging with them their children, their dogs, their picnic baskets, their bicycles, and, of course, their suntan lotion. Such visitors may be surprised to find that there is a population of very much “other” people, who make that same journey, but in the reverse direction, and not just once or twice in the holiday season but day after day and week after week, throughout the year, and not only when the water is as bland and blue as the French Riviera, but occasionally when it comes crashing up over the bow and drowning the decks, so that it’s safer to huddle in the cabin at the centre of the ship.

On just such a day as that, in the middle of February, I stand shivering at the Island ferry docks behind the towers of the Harbour Castle Hotel, waiting for the Island ferry to take me across to Ward’s Island. As the wind whips around the ferry gates, survival mode kicks in and we passengers huddle together for warmth and company. We are an oddly diverse collection of Torontonians: school children, burdened with with snowsuits and backpacks, alongside a cadre of intrepid winter cyclists, mostly middle-aged Island residents, who are in turn weighed down with a week’s groceries strapped to every possible place on their bikes and bodies.

The gates of the ferry terminal are hauled back as the old Ongiara bumps up with a thud against the harbour wall. We step onto the solid little ship and haul open the ice encrusted door to the cabin. With a strong sense of relief we settle down to relax, cocooned by the sudden warmth. Choppy waves lurch up and down outside the frosty windows. Seemingly so far off at first, the Island begins to emerge from the far tree-lined shore.

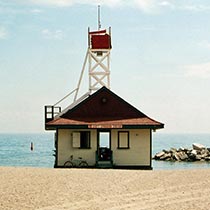

At the Ward’s Island landing the creaky ferry platform is eased into place and the crowd moves away from the ship in all directions, only to be slapped and set back sharply for a moment by a blast of arresting, arctic cold. The Island always seems at least ten degrees colder than the mainland in winter. Down on the beach by the ferry landing the sun comes out from behind the clouds. Shining through the ice cakes that have stacked up on the hard-packed sand, it turns them as transparent as glass. Farther down the beach an old rowboat lies at the water’s edge. Someone has forgotten to take it in for winter. Frozen in time, it remains poised at the water’s edge, patiently awaiting its launch toward the towers of the emerald city . . .