The Beach

Canada’s premier film director Norman Frederick Jewison was born in the Beach in 1926 and was raised overtop his parents’ dry goods store and sub-post office in the 1930s. When he left the district some years later, he took along the many life experiences he had gained there as a child. Here are some of his thoughts, as told to me in an interview in July 2009 when I was preparing this book.

JF: You mention the Beach a number of times in your autobiography, This Terrible Business Has Been Good to Me. Did the place where you grew up play an important part in your development as a creative artist?

NJ: I think anyone’s early experiences, probably from the age of five right through until they’re twenty years old, are extremely important in forming the values and everything else that makes up personality, so you can always look at where someone lived their early years as an indicator of influences . . .

JF: In your autobiography you describe yourself as “a keen observer of human nature.” I’m wondering whether living in such a place as the Beach gave you an early insight that enabled you later on to tell the stories that you’ve told?

NJ: Absolutely. My father was the Postmaster of Substation 10 and at sixteen years old I was sworn into the Post Office, which meant I could write postal notes and registered mail and take responsibility for all kinds of stuff . . .

JF: Do you think of yourself as having grown up in a village, or did you grow up in Toronto?

NJ: Oh I grew up in a village. Everybody knew each other and my parents had a store and a sub-post office, which meant that we were a centre. If you wanted stamps, you wanted to mail a letter, you wanted to, you know, mail a parcel and you lived anywhere between Woodbine and all the way over to I’m sure past Lee Avenue somewhere, everyone came to our store, at Kippendavie and Queen.

……….

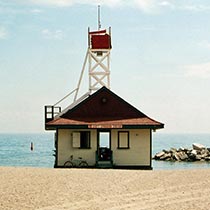

NJ: . . . The whole Beach has now become “yuppified.” I mean it’s become a desirable place to live. When I was there, the houses were almost like cottages. It was a cheap place to live. Nobody wanted to live in the east end. It was kind of a working class area, and the people were kind of rebellious, and they were kind of suspicious of foreigners and all of that . . . but they had the Lake — and they had the Boardwalk and they had Kew Beach Park and they had the racetrack. And these things were all very important to them.

JF: So what about the connection to water and the landscape?

NJ: Oh, I think that was a very strong influence, at least it was on me and the group I hung out with in that area on Kippendavie and Woodbine and Buller Avenue and Kenilworth, because we had canoes. The big thing was to get a canoe when you were about twelve years old. We’d camp out and we’d paddle down to Highland Creek and around the Rouge there, because it was wild then and we would literally camp out in the wild and the open with the Boy Scouts or just with others. So we spent a lot of time on the beach. We were thrilled when the water started to warm up. And everybody was swimming when it was freezing cold.

Then there was the Balmy Beach Canoe Club. That was a centre of teenage activity — where everybody wanted to be. They wanted to paddle for Balmy Beach because water sports and canoeing and racing and war canoes and paddling were big things down there. It didn’t cost anything and again it was the Lake that pulled us together.