Irish revolutionary Pádraig Pearse said, “Tír gan Teanga, Tír gan Anam.” In English, “A country without a language is a country without a soul.” Irish, the native tongue of Ireland, continues in the present to be poignantly expressed in the mythology, poetry and language of the land.

18th and 19th century Irish immigrants to Ontario carried their aspirations and dreams with them, and cultural memory informed through millennia of Indigenous lived experience on the land. This experience profoundly affected their relationship to place, sense of belonging, and in some instances, identification with other colonized societies. Thought you’d like to see some of the images that illustrate this idea for me, and figure in the second chapter of my new project, “Field”.

Above: Benbulben, County Sligo, Jane Fairburn

Above: Benbulben, County Sligo, Jane Fairburn

I shot this image from the roadside — it captures only a sliver of the mystical significance of one of Ireland’s great mountains. Benbulben figures prominently in Irish mythology and the poetry and prose of W. B. Yeats.

Above: “Lady Lavery as Kathleen Ni Houlihan”, John Lavery, National Museum of Ireland

So rooted is the land in the concept of Irish identity that the mythical Kathleen ni Houlihan was set against the Killarney lakes and fields on the first Free State banknotes.

Above: “Gorta”, Lillian Lucy Davidson, “Coming Home: Art & The Great Hunger”

The Great Famine in Ireland (An Gorta Mór), from 1845 to 1852, is now viewed as the most significant human tragedy of the nineteenth century. More than 1 million Irish people died, many of them buried in mass graves on Irish soil. Dispossessed from their land, even greater numbers sought refuge in America and the British colonies, including Canada. Their experiences contributed to a strong sense of cultural memory among their descendants, and how they view the land in their adopted countries.

Above: “A Connemara Village”, Paul Henry, National Gallery of Ireland

This lovely painting captures the power of the landscape of “The West” of Ireland (Connacht). Though no area of the country was spared the devastating consequences of the Great Famine, the West is one of the great portals through which many nineteenth century Irish travelled to Ontario.

Above: Famine Wall, Termon House, County Donegal, Jane Fairburn

During the Great Famine, the dispossessed and starving were paid a pittance to build stone protective walls around English plantation houses. This is a detail of a famine wall I shot at Termon House, County Donegal.

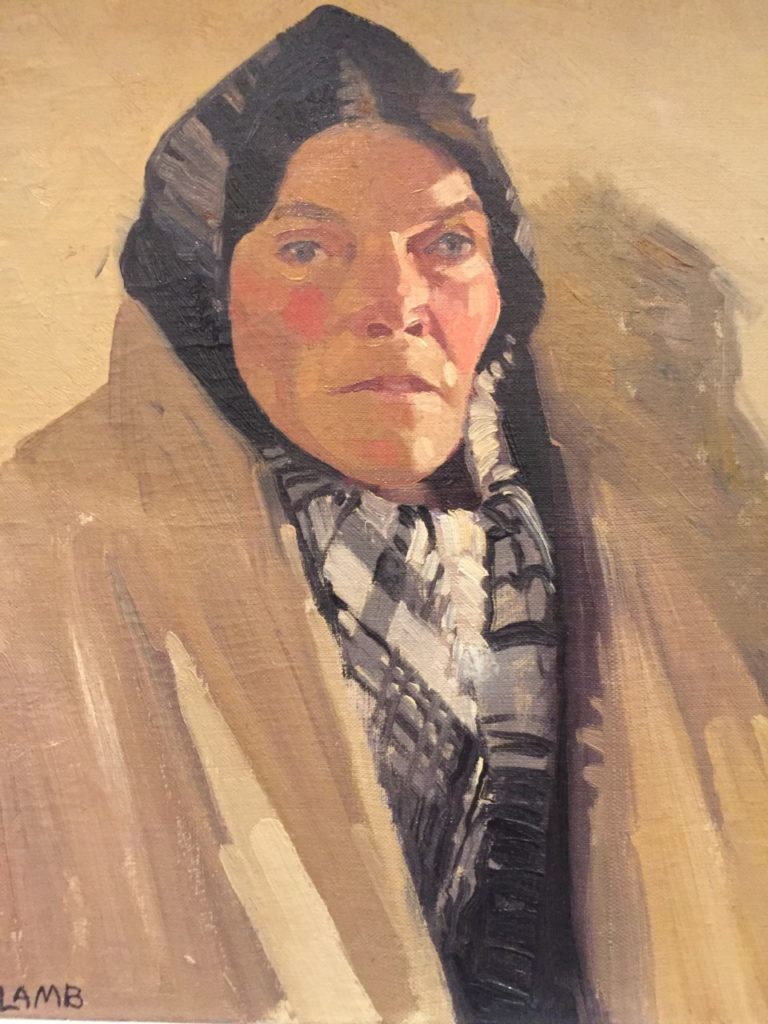

Above: “Nan Mhicil Liam”, Charles Vincent Lamb, National Gallery of Ireland

I explore the interface and connections between Irish and Indigenous cultures in “Field”.

Above: “Launching the Currach”, Paul Henry, National Gallery of Ireland

The sea and the shore are still an integral part of life in The West. This image captures men of the island of Achill, County Mayo. Groups of people in Achill maintained a nomadic lifestyle into the twentieth century, and were wary of having their image reproduced in any format.

Above: Gathering seaweed on the beach, County Donegal, Lisa Martin

Seaweed has traditionally been used as a source of fertilizer, medicine and even food in Ireland — it also is lovely in a bath!

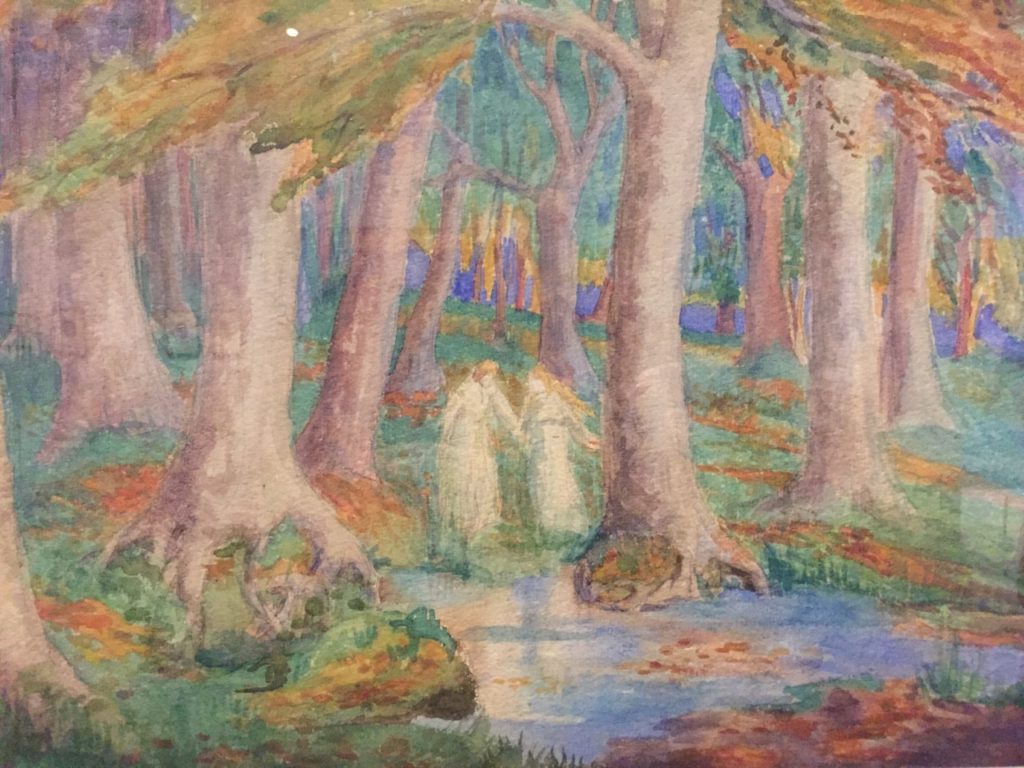

Above: “Forest Pool, two figures in white, male and female”, Countess Markievicz, National Museum of Ireland

The Countess Markievicz was a central figure in the Irish Civil War and cultural revival. She sketched this image while imprisoned after the Easter Rising in 1916.

Above: “The Singing Horseman”, Jack B. Yeats, National Gallery of Ireland

The horse remains a powerful symbol of connection to the land for the Irish, second only to the bull.

Above: Donegal beach, with Norman Keep in distance, Jane Fairburn

Ireland’s cultural calling card is its Celtic past, but this, of course, is only part of the story. Ireland, like all of Europe, is the product of successive invasions, including from the Normans and the Vikings. Each of these invasions left its mark on the nature and character of Ireland, and its people.

Be sure to give my Facebook page, Chronicles and Relics, a Like! That way you can follow the progression of the project and check out more videos and photos of my Irish adventure!

All images: National Museum of Ireland, as noted, Jane Fairburn © and Lisa Martin ©.

A Word about Culture and Belonging

Did you know that access to culture in Ireland is free? Irish national or not, any person is entitled to free access to all museums in Ireland, and the staff bends over backwards to make your experience accessible and enjoyable. The museums are truly for the people — such an enlightened way to think about the promotion of cultural belonging and identity!