Hello friends — it’s been a while.

On the eve of Saint Patrick’s Day, I thought you might like to read a piece I wrote, previously published by Providence Healthcare (part of Unity Health, Toronto), on our city’s connection to the Great Famine, and the role the Sisters of Saint Joseph played in administering to Toronto’s Irish.

Níl cara ag cumha ach cuimhne. (Memory is grief’s only friend.)

The Ulster Irish have a word for it: cumha [KOOaye]. It captures the deep melancholy and bone-aching sadness that reside in the yearning for home. And that yearning was fostered through an unanticipated, perilous journey. British colonization of Ireland in the seventeenth century and rapid population growth set in motion a series of events that, by the nineteenth century, made the vast majority of Irish, at best, tenants on their own land. Successive failures of the potato crop, a primary food source, reached a crescendo in 1847, and the Irish people — collateral damage to British Imperialist policy — resorted to chewing on tree roots to survive.

Though immigration began earlier, a million and a half starving and indigent Irish (mainly, but not exclusively Catholic) were left with little choice but to clamber down into the dark recesses of coffin ships for the New World. Raw grief was their companion, losing as they did their language and thousands of years of connection to the land and the people they loved. And they were the lucky ones. Many thousands of others never again saw shore. Mothers, fathers, babies, sisters and brothers, often stricken with typhus, or “ship’s fever,” were committed to the sea. Over a million others lie in mass graves beneath the sod of the Emerald Isle.

“Gorta,” Lillian Lucy Davidson, From Art & the Great Hunger Exhibition, Dublin Castle, 2018.

The Feast of St. Patrick on March 17, commemorating Ireland’s patron saint, is an opportunity to reflect on An Gorta Mór, the Great Famine of 1845–1852, and the role the Sisters of St. Joseph of Toronto played in the aftermath of the heartbreaking tragedy. It is a story rife with loss and longing, but also of compassion and assistance to those whom the Sisters called “the dear neighbour,” the city’s first visible immigrant community. The result, in a matter of two or three generations, was full Irish integration into the fabric of a city with a strong and steadfast Protestant ascendancy.

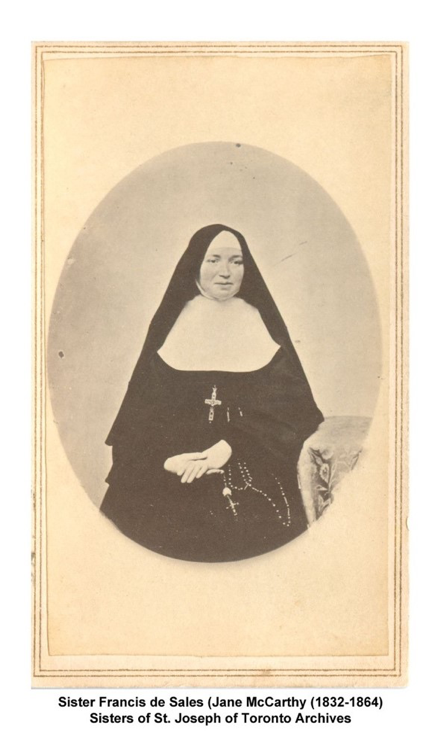

Sister Francis emigrated from Clonakilty, Co. Cork, Ireland, in 1848. She lost a brother and sister in Toronto to what was likely tuberculosis, before becoming the city’s first resident to enter the congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph in 1852. She devoted the rest of her life to caring for orphans, widows and immigrant women. Courtesy the Sisters of St. Joseph Archives.

SUDDENLY, it’s cool to be Irish. While there’s some truth in the statement that the Scots invented Canada, there’s also this truth: the Irish have greatly contributed to unlocking Canada’s creative potential. Saint Patrick’s Day, once a welcome day off from the strict observance of Lenten obligations, has now been transformed by the Irish diaspora into a worldwide, flat-out celebration of all things Celtic. But there’s another story of the Irish, beyond the genial, fun-loving aspects so often on display. Turn back the clock to mid-nineteenth century Victorian Toronto, and a tenebrous story emerges, redolent with human suffering.

Disneyland in Shanghai, China, going “green” for St. Patrick’s Day. thesun.ie

In the summer of 1847 in Toronto, it was definitely not cool to be Irish. At that time, the city was a backwater colonial town of some 20,000 mainly Protestant souls with little access to social services. The poor and mentally ill were often imprisoned, while orphans, the infirm and diseased frequently clung to life through the charity of others. Add to this the Industrial Revolution that was fuelling the economic growth of Upper Canada. Regular folk lived out their days in cramped quarters next to factories that spewed plumes of toxic smoke, with little healthcare available for the average worker.

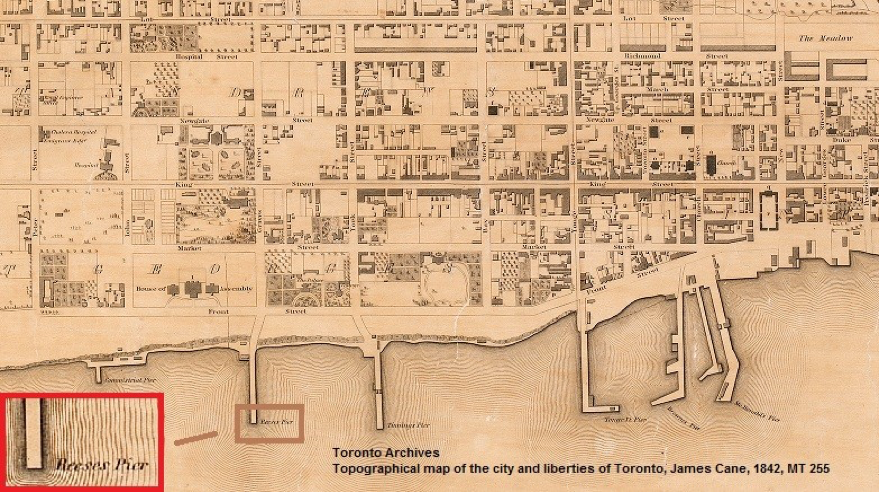

So when the ice retreated from Lake Ontario and a deluge of desperate Irish, riddled with typhus, began disembarking at Rees’s wharf below what is now the CN Tower, they weren’t met with waves of adulation. (John Strachan, the Anglican Bishop of Toronto, in an 1848 letter reported that approximately 40,000 Irish had moved through Toronto in 1847 alone; letter cited below.) Add to that the cultural difference. The Irish disembarking at Toronto were, in the main, a deeply rural people who retained a rich oral history and an indigenous connection to the land. The vast majority of them lived in large family groups and had no experience with mechanization, let alone city life. Though then British subjects, they might as well have landed on the moon.

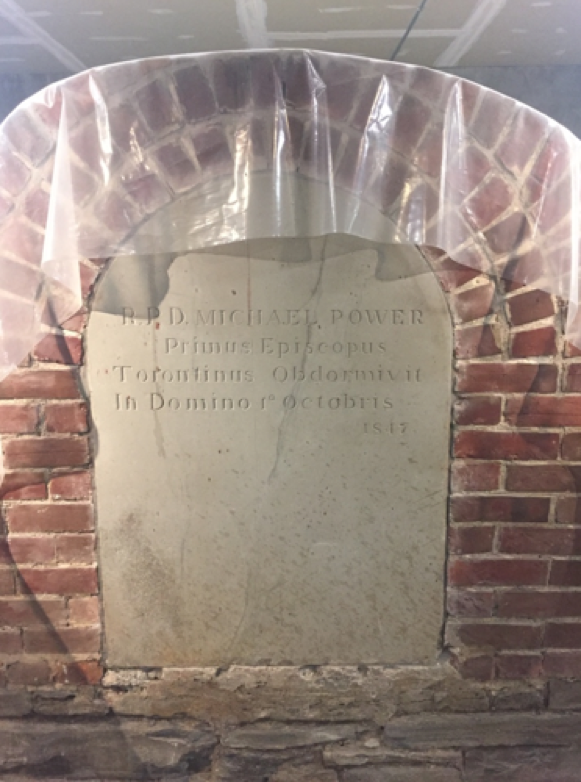

The city fathers, hard-scrabble Orangemen to the core, took a very practical approach to a problem that could have easily unhinged the city. The grievously sick were provided for. Those with blackened tongues (the telltale sign of typhus) made an orderly, funereal procession up John Street to the fever sheds, from which many never emerged. Both Protestant and Catholic heroes stepped into the void to address the crisis. Roman Catholic Bishop Michael Power, born of Irish parentage, ministered to the sick and dying and administered last rites to the faithful in the sheds. He was the first to succumb. His splendid St. Michael’s Cathedral Basilica was under construction at the time of his death. Power was followed to the grave by the primary physician who worked night and day in the sheds, and ultimately gave his life to the cause — the brave Dr. George Grasett. His colleagues and assistants, among them nurse Susan Bailey, would soon follow.

Harp brooch discovered at site of the Emigrant Fever Hospital (formerly the General Hospital)

and fever sheds, 2006. Courtesy Archaeological Services Inc., Toronto.

The crisis of 1847 did not repeat itself the following year. Stringent taxes were imposed on ships entering Upper Canada in 1848 with passengers who required quarantine. Irish immigration continued to Toronto, though at a slower pace, with far more ships docking at Atlantic ports, including New York City.

“We are still suffering under a great menace of poverty, and the number of widows and orphans must be provided for,” wrote Bishop John Strachan to Waddilove, April 27, 1848. (Cited in Stage 1 Archaeological Resource Assessment of 326-358 King Street West, Toronto.)

The effects of the famine lingered. Recurrences of typhus and persistent bouts of cholera and consumption (tuberculosis) made orphans of an alarming number of children. Bereft widows were left with starving mouths to feed. Unimaginable social change brought many to the brink of despair, and mental illness rose to the fore. In 1851, Bishop Michael Power’s successor, Armand-François-Marie de Charbonnel, invited the Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia to send a group of women north to Toronto to minister to the city’s most vulnerable.

The St. Joseph’s order originated in France, and the centuries–old mandate of the Sisters was clear: to show compassion to those most in need, regardless of creed or nation. In keeping with the mission, the Sisters initially managed the Widows and Orphans Asylum on Nelson Street (now Jarvis Street). The orphanage, donated by local entrepreneur, philanthropist and convert to Catholicism John Elmsley, began as a multi-purpose institution: it initially served as the Sisters’ residence. In 1852 alone, the Sisters took in and cared for 60 Irish women sent to Canada by the Poor Law Commissioners of Ireland until employment and full-time residences could be found for them. The Sisters were from the earliest years also directly involved in Catholic education. Schools were established in 1852 on Lombard Street and in 1853 on St. Patrick’s Square and Power Street.

John Elmsley, Bishop Power, and many other prominent laity and religious of the famine era

lie in the crypt of St. Michael’s Cathedral Basilica (under renovation at the time of this photo). Photo © 2018 by Jane Fairburn.

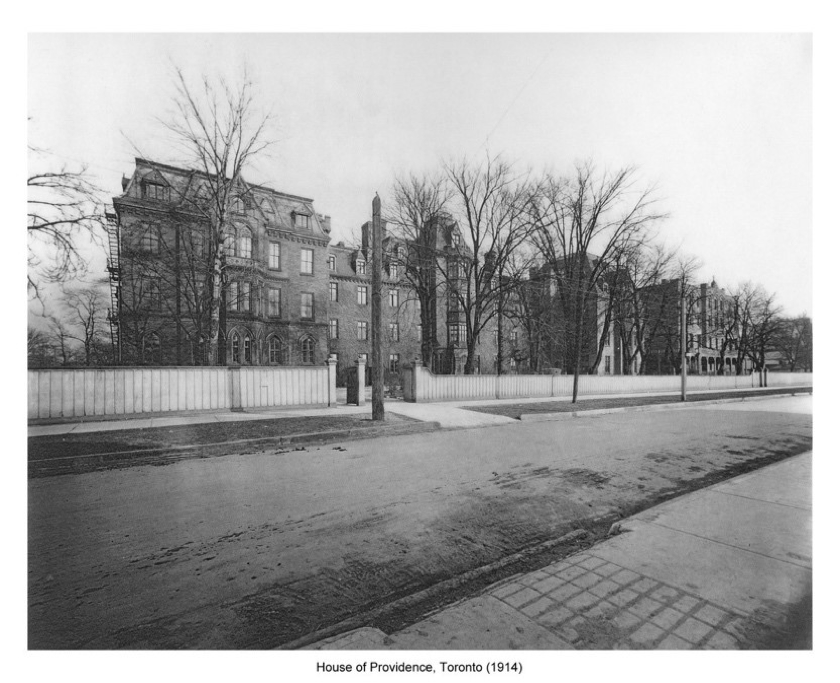

Within six years, the doors of the House of Providence were opened on Power Street. The institution ministered to the sick, the infirm, the elderly and widows and orphans. For years, it was run independent of government assistance of any kind. Residents assisted to the extent that they were able, and Torontonians of all religious affinities, as well as local farmers, gave generously. Mary Birney, whose husband was lost at sea, was the first resident of the House, and stayed on. The Annals of the House of Providence say of Mrs. Birney, “to devote her life to work for the poor and nobly she carried out her resolution. She was offered remuneration for her services, which she steadfastly refused.”

House of Providence, Toronto, 1914.

Courtesy Sisters of St. Joseph’s Archives and the Archives

of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto (ARCAT).

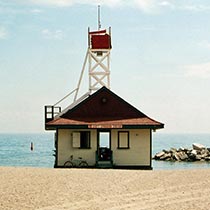

Eventually, the Sisters established their own farm, first in the Beach district in the nineteenth century, and later, in the early twentieth century, in the Township of Scarborough near the present-day intersection of Warden and St. Clair avenues, to provide for the nutritional needs of the residents and others under their care.

Providence farmer Basil Majowski brings in the hay.

House of Providence Farm, Township of Scarborough.

Courtesy Sisters of St. Joseph’s Archives.

In 1962, the House of Providence closed, and all residents were moved to Providence Villa and Hospital (now Providence Healthcare). Toronto was on the verge of another massive shift. Within a decade, the city would see a surge of immigration from around the world.

To coin an Irish phrase: the Sisters were, and continue to be, “some women.” Over the course of almost 170 years in Toronto, they have cared for a diverse population of immigrants, established and run hospitals, including Providence Healthcare, St. Michael’s and St. Joseph’s (together now known as Unity Health Toronto), and continued their task of teaching.

While few of them walk the halls today, their legacy of caring continues, begun in the aftermath of the greatest human tragedy of the nineteenth century.

Many thanks to Linda Wicks, Archivist of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Toronto, Ron Williamson of Archaelogical Services Inc., Beth Johnson, Mission Integration at Providence Healthcare, St. Joseph’s Health Centre and St. Michael’s Hospital, and Cathal Ó Manacháin of Belfast, Ireland. —JF

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

This is a wonderful historical sketch of the Irish Potato Famine, and of the roots of the Sisters of St. Joseph in responding to the desperate needs of impoverished, sick, dying Irish immigrants. It also tells about the founding of Providence Healthcare through to the recent administrative amalgamation of Providence Healthcare, St. Michael’s Hospital and St. Joseph’s Hospital (now Unity Health Toronto). I am currently a volunteer at Providence Healthcare, at St. Clair and Warden Avenues–where so much of Providence’s and the Sisters of St. Joseph’s history took place. I will send this to my friend in Ireland who has sent me some of the history re. the Irish emigrant ships that brought so very many Irish immigrants to Toronto and Canada. Thank you, thank you.

You’re welcome, Michael – glad you enjoyed it!