Septembers in Ontario, like the vine, are perennially bittersweet. Children, still kissed by the summer sun, hasten off to the serious business of school. Routine and order reign, as parents get down to the task of making a living. Cooler days give way to blacker evenings and the certainty of hard frost, while maple leaves darken to vermilion. Winter looms.

The melancholy that is September has brought change to our city garden. As I write, a gnarly horseradish sits near the edge of my desk, atop a bunch of spindly and misshapen carrots. Despite our near-misses and our losses, including the demise of the ornery-yet-lovable-Helga-the-hen, the urban farming project we began on the edge of the lake this summer was a source of great fun and joy.

More spindly City Hick carrots! © Jane Fairburn, 2020.

More spindly City Hick carrots! © Jane Fairburn, 2020.

There’s something primal and satisfying about growing and eating your own food — I say this knowing that I’m hardly alone in tracing a pathway back to the land through vegetables, compost and livestock. While 4,500 kilometer food chains of oil, gas and diesel feeding Toronto faltered and sputtered, many seed companies could not keep up with demand this year. Torontonians avoided big box grocery stores and shopped less. Those with fewer resources explored alternatives for fresh food. Public city garden plots were scarce or filled to capacity.

Faced with months of lockdown, many of us yearned for the chance to put our hands into the earth and restore a sense of unity and belonging. The fact is that the pandemic has lifted the veil on a compelling need in Toronto for greater sources of sustainable agriculture: locally grown, responsibly raised, affordable food.

City Hick cantaloupe, © Jane Fairburn, 2020.

City Hick cantaloupe, © Jane Fairburn, 2020.

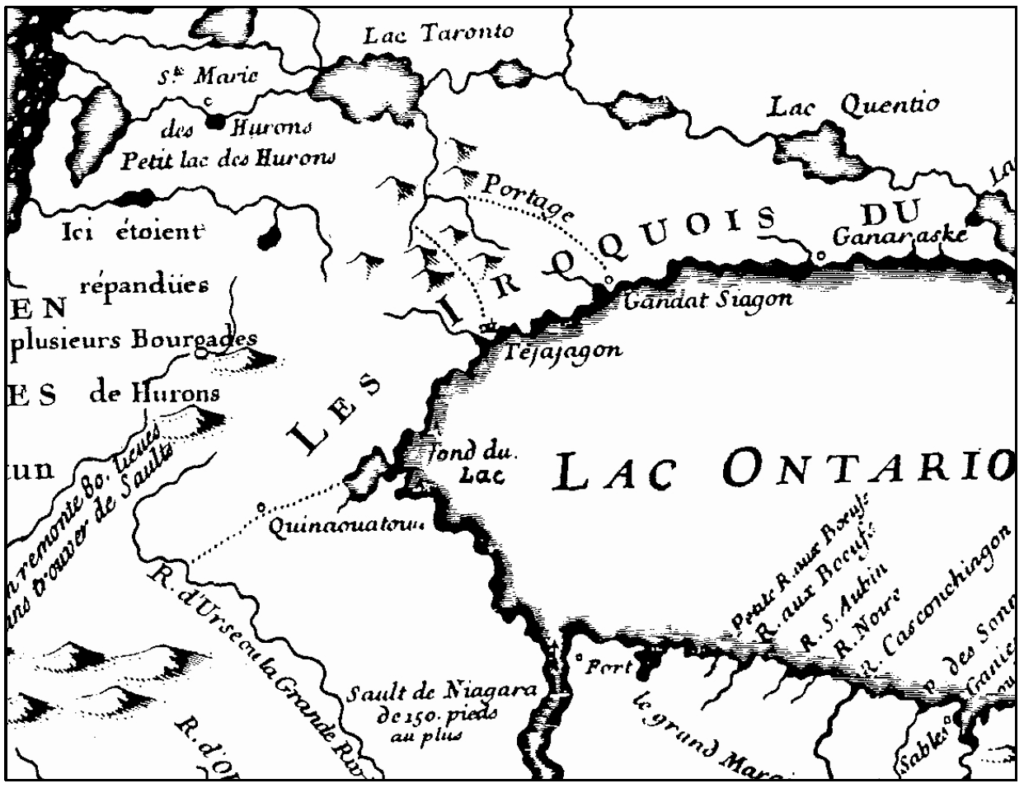

Many may be surprised to know that the Toronto region has a long and storied tradition of growing local food that pre-dates European settlement by many hundreds of years — Iroquoian horticultural societies began farming in the lower Great Lakes region about 1,100 years ago. In the fourteenth century, there were a number of agricultural-based communities on the major waterways that flowed down to the shore at what is now Toronto.

In the seventeenth century, the Hauedenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy began their northward expansion from present-day New York State across Lake Ontario. By the early 1670s they had established a series of villages at the outlets of many of the rivers that emptied into Lake Ontario, from what is now Prince Edward County in the east, to the vicinity of Burlington Bay in the west. Two communities were established at what later became the City of Toronto: Ganatsekwyagon near the mouth of the Rouge River and Teiaiagon, above the outlet of the Humber. These villages commanded the eastern and western branches of an ancient Indigenous portage route to the Upper Great Lakes and interior of Canada, known as Le Passage de Toronto (in later years, Carrying Place Trail).

Haudenosaunee colonial expansion didn’t stop at the foot of Le Passage de Toronto, or for that matter, the foot of the other river routes associated with the villages to the east and west. Theirs was a vast territory, from the fertile southern shores of Rice Lake, through to the northern limits of the rich hunting grounds of the ‘Land Between’, at Midland and Penetanguishene, on the southern shore of Georgian Bay. (Much of the Confederacy’s territory north of Lake Ontario lies within what we now refer to as the Greater Golden Horseshoe Region (GGHR).[1]

The Bellin map, 1744, shines an 18th century lens on the Greater Golden Horseshoe Region, with some of the Haudenosaunee villages, including Ganatsekwyagon and Teiaiagon noted. Le Passage de Toronto ended at the Holland River, which flowed into Lake Simcoe (‘Lac Taronto’).

The ‘Iroquois du Nord’ grew food where they lived. An efficient system of agriculture near the mouths of the Rouge and Humber Rivers produced acres upon acres of corn, beans and squash (known as the Three Sisters), and sustained villages of 500 to 800 people and various other offshoot communities.

The irony is that in 2020, while many Torontonians buy their corn, beans and squash from Mexico, the United States and Chile, 100 percent of that food was produced on Toronto’s doorstep in 1675. And while increasing numbers of small-scale farmers within the GGHR clamour for access to local Toronto markets, a whopping number of other food producers ship their harvest offshore, to places as far flung as China and Japan. It seems to me there’s something askew with the concept of buying carrots from California when acres of them are being raised a short distance from your own backdoor.

Don’t get me wrong: I love my avocadoes, bananas and pomegranates in the midst of the bleakest months of winter, and I’m not planning on giving them up any time soon. What I’m talking about is the prospect of increased access and growing opportunities for food that is naturally capable of being raised locally and regionally. Given the current stress on global supply chains and the inevitable emissions they cause, and the fact that more than one in every ten Torontonians face food insecurity issues, we have to ask ourselves: How the hell did this happen? And better yet: What can we do about it?

Well, first, there’s this. Agriculture is not a zero-sum game. Even the Haudenosaunee had their issues with food production. The persistent planting of the Three Sisters gave the Seneca about 20 good years on the land before its mineral and organic resources were exhausted. European farming practices brought apparent solutions to sustain soil quality and boost yields through increasingly complex methods of industrialization.

Fertilization was adopted, later followed by the use of chemical pesticides. The land, previously worked by horse and plow by many of our ancestors, moved to tractors and excessive tillage, which led to erosion, which only demanded further use of chemical supplementation. The miracle of nineteenth and early twentieth century railways opened up access to offshore markets. Larger farms were needed with fewer hands and increasingly more complex and monstrous machines. Single crops began to rule the day.

. . .

Though some might point to the post-Second World War period as the beginning of the decline of the family farm in eastern Canada, its demise actually began decades earlier, in the fledgling decades of the twentieth century.[2] A particular perspective had taken root — perhaps more prominent in English Canada than in La Belle Province. Somehow, through the industrialization process, we began to lose our love of the land and started to see it as a commodity. When the rising economic engine that was Toronto came calling, offering more money for less backbreaking work, country folk in the surrounding region began to walk away from the cathedral-like barns and towering hay mows of their ancestors.

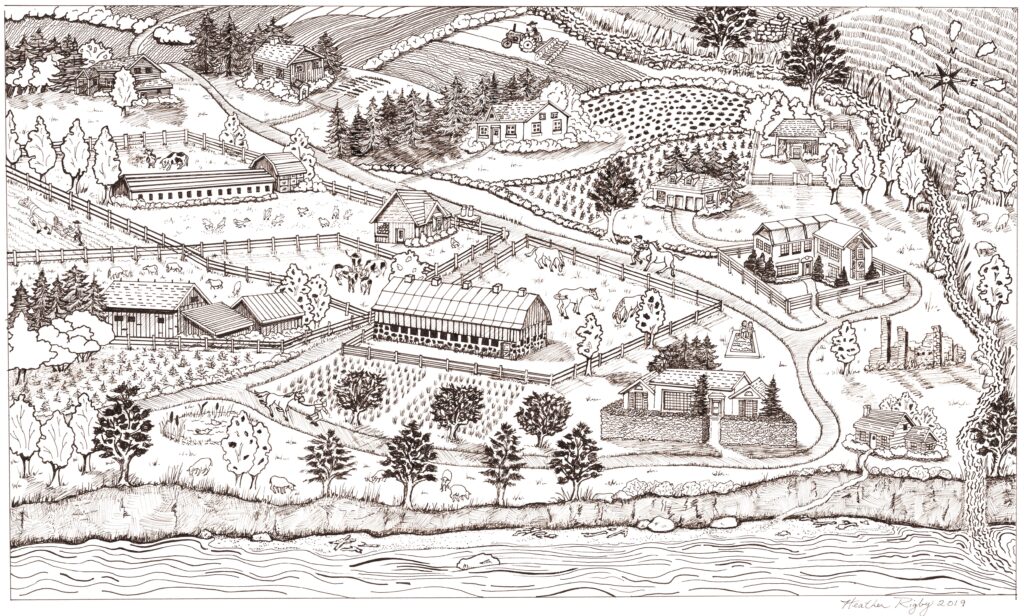

Toronto lawyer, author and industrialist William Henry Moore established Moorlands, his idyllic, 200-acre mixed farm, in the vicinity of the former Iroquois village of Ganatsekwyagon in 1912.[3] Located in the rural community of Rosebank, Pickering Township, at the waters’ edge, it stood as an example of regenerative, integrated mixed-farming at its best. The farm was in its heyday from the 1920s to the 1940s, producing milk, eggs, cream, pork, beef, chicken, and lamb for local markets.[4]

Conceptual drawing of Moorlands. © Heather Rigby, 2019.

Conceptual drawing of Moorlands. © Heather Rigby, 2019.

Moorlands was my mother’s home. The loss of that land has inspired my upcoming book, Moorlands: An Ancestral Memoir of Loss and Belonging. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Was Moorlands romantic? Yes. But beyond the artesian well that watered the heritage fruit trees, the frozen sheets of chiselled Lake Scugog ice that cooled the dairy in scalding summers, and the glorious pigs that spent their last days fattening on truckloads of Mr. Christie cookie crumbs, the farm achieved something more than beauty and utopia. Moorlands celebrated Ontario’s historic connection to farming and the land, through the generations, and indeed, the millennia.

Expropriation procedures, begun by the then Metropolitan Toronto Conservation Authority, eventually resulted in the sale of Moorlands to that body in the mid-1960s. (The property is now known as the Petticoat Creek Conservation Area.) A few years later, the Class 1 farmland a short distance to the north of the farm became the subject of a sinister and controversial expropriation process which remains unresolved to this day. In 1972-3, the federal government expropriated 18,600 acres of farmland, natural habitat and waterways across three townships to build a second international airport for Toronto. While more than half of the original expropriated area has been subsumed into Rouge National Urban Park, 6,700 acres of Class 1, fertile farmland in what is now the City of Pickering remains in the hands of Transport Canada.

This despite a report from international consulting giant KPMG, that in March of this year determined an airport on the Pickering Federal Lands is not required within the current planning window that extends to 2036. Nonetheless, the fate of the Lands are slated to remain in a further state of limbo until yet another airport assessment in undertaken. The once lively hamlets of Brougham and Altona, a stone’s throw from Toronto and in former years the backbone of the farming community, radiate a ghost-like presence now. Heritage barns and proud farmhouses stand abandoned in the wind and the rain, victims of demolition by neglect — a sad metaphor for our disappearing rural heritage.

The once stately Bentley-Carruthers House is now located inside the Rouge National Urban Park border. It is an elegant example of Ontario post-pioneer brick construction, and a powerful symbol of the half-century long struggle to protect the Lands. © Jane Fairburn, 2018.

The once stately Bentley-Carruthers House is now located inside the Rouge National Urban Park border. It is an elegant example of Ontario post-pioneer brick construction, and a powerful symbol of the half-century long struggle to protect the Lands. © Jane Fairburn, 2018.

W. H. Moore, in an interview with the Globe on October 23, 1918 said that, “…only when loved for its own sake, does the land yield its fullest benefits to mankind… it may be that having deserted the farms we cannot permanently maintain ourselves in the city.” Those were prescient words, when viewed in light of the opportunity for agricultural renewal that is presented by the Pickering Federal Lands today. The current plan, put forward in a 2018 report commissioned by Land Over Landings, the group that opposes the airport, is no pipedream. A Future for the Lands: Economic Impact of Remaining Pickering Federal Lands if Returned to Permanent Agriculture outlines a road map for the establishment of sustainable agriculture that will feed the Toronto region and address issues of climate change, food insecurity and responsibly raised food.

Pickering Federal Lands, © Jane Fairburn, 2018.

Specifically, 30-year, renewable leases are recommended to encourage infrastructure investment, and an integrated system of farms, businesses and communities. The vision is that ‘North Pickering Farms’, adjacent to North America’s largest urban park, would become a primary agricultural focal-point for Toronto. Literally accessible to the downtown core by public transit, the Lands would act as a food hub for mixed, small scale farms providing a variety of fruits and vegetables for diverse communities. The Lands are also envisioned to be a leader in eco-tourism with a strong educational component — a research facility on climate change adaptation is part of the plan. The bonus is that resultant economic increases in the York-Durham Region are anticipated to be in excess of 125 million dollars per year.

Prior to the Covid crisis and the KPMG report, the prospect of an airport on the Pickering Federal Lands had once again gathered steam in 2018. In April of the following year, I attended a talk at the Toronto Region Board of Trade, where the idea of an aerotropolis was floated for the future of the Lands. Experts could barely contain their glee as they described nirvana: a bulldozed landscape cast in concrete, where workers lived in neatly contained corridors and food was grown in bunkers, adjacent to airport runways. What left me the most agog were the large numbers of people in the room from various points of view and economic sectors who simply didn’t flinch at the plan.

Which got me thinking of something else. More than courage will be required to successfully develop the Pickering Federal Lands as an agricultural centre for Toronto. What is needed is a fundamental shift in perspective. Perhaps the first task is to get back to the future and collectively rediscover the value of the culture of agriculture — to learn from the experiences of the Haudenosaunee, and uncover the stories of our own ancestors, who in the not-so-distant-past worked this land, or the faraway fields of distant places, still treasured in the heart.

Only then we will be inspired to put our hands back in the earth. Only then will we learn how to love this land.

Many thanks to Alexis Edghill Whalen (Land Over Landings) for our wide-ranging discussions, and a treasure trove of information on sustainable agriculture.

“Return from the Harvest Field”, Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté, 1903.

National Gallery of Canada.

[1] During the course of the research for my current project, Moorlands: An Ancestral Memoir of Loss and Belonging, I’ve had the benefit of reviewing several excellent papers on Ganatsekwyagon and the Iroquois du Nord. Among them are Tom Mohr’s “The Gandy Project: Locating the Historic Seneca Village of Gandatsetiagon”, 1998, Dana Poulton’s draft paper, “The Bead Hill Site: A Late Seventeenth Century Seneca Village on the Lower Rouge River, Pickering Township, Ontario”, presented at the 46th annual symposium of the Ontario Archaeological Society, November 1-3, 2019, and Archaeological Services Inc.’s “Southeast Collector Recreational Enhancements, East Branch of the Toronto Carrying Place: An Historical Overview”, (otherwise known as the Rouge Trail Report), March, 2011.

[2] By 1921, there were almost half a million more people living in urban communities in Ontario than in rural areas. See: Ninth Census of Canada, 1951, vol. 1, Table 13.

[3] In 1925, Moore stated that 2,500 bushels of grain alone were gathered from the fields of Moorlands, The Toronto Daily Star, September 7, 1926.

[4] W. H. (Billy) Moore became the Liberal Member of Parliament for Ontario in 1930, holding his seat until retirement in 1945.

{ 4 comments… read them below or add one }

Hi Jane, if you are ever looking for enthusiastic help on your farm, let me know. I’m currently doing egg hens, bees and veggie gardens in the Guild. The veggie gardens are definitely the most challenging lol. I’ve been looking for a farm of my own for years now but cant seem to convince the hubby that it’s an awesome risk he should take. Ah well, might have to go it alone :).

Thanks for the great article!

MariLynn

Hi MariLynn — amazing that you’re doing all of that — how fitting to be doing so in the former Township of Scarborough, with its rich agricultural heritage. Bee keeping in an urban setting? Wowza. Let’s talk!

So much to learn from you and better yet get active about shaping our landscape!

Thanks, Jennifer.

Every tilled field, every garden bed planted is a shaped landscape. All of us leave imprints on the earth.