Gardens, hen and hoop house, Meadowcliffe Bluff. © Jane Fairburn, 2020.

Come to think of it, I’m pretty much sure I’ve always been a city hick. Like many Canadians, my story of ‘back to the land’ is rooted in the experiences of my ancestors and married to the policies of British Imperialism and colonization that radically transformed much of the modern world. The Celtic peoples of Scotland, Ireland and Wales were the first societies in Europe to experience land displacement and loss of community and language as the result of British colonization. Ironically, many of those same people were among the millions of Europeans who in later generations crossed the sea and participated in the further unfolding of the saga, ushering in a period of cultural subjugation and technological change in the new world.

My great-great-grandfather was Scottish industrialist George Hope Bertram, M. P. for Toronto Centre and the proprietor of Bertram Engines on Toronto Bay. George, along with his brother John, built some pretty impressive floating palaces in their day, including the elegant Toronto passenger steamer, and the little Hiawatha, that still graces Toronto Bay as the tender for the Royal Canadian Yacht Club. But George, despite all his accomplishments, was pretty much a city hick too.

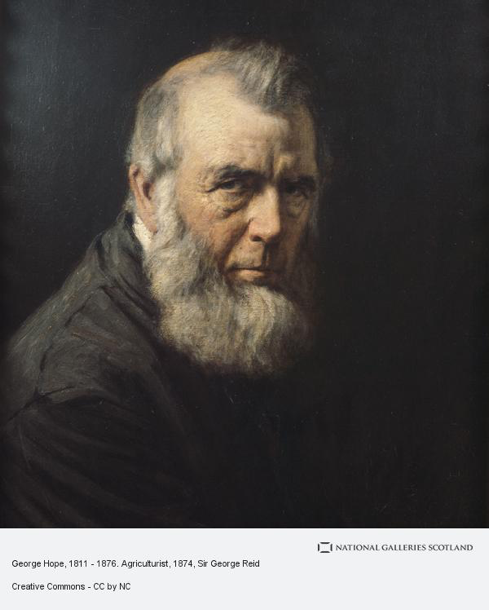

Bertram’s father Hugh had humble agrarian roots. He was the steward on the model farm of the original George Hope, the fierce-eyed tenant farmer, agriculturalist, and land reformer of East Lothian, Scotland. The heavy, water logged clay soils of Fenton Barns just outside Edinburgh were pure misery for tenant farmers, who for generations eked out a living through subsistence agriculture and rents paid to the gentry. Among Hope’s improvements was the manufacture of clay tiles from the ‘muir’ bogs. (‘Muir’ is the Scots name for moorlands, or wild, uncultivated fields. It’s also the Scots Gaelic word for the sea). Those same tiles, shaped from the clay, were then dried, and used to drain the fields. That practice, along with deep cultivation, soil amendments, and the promulgation of rights and responsibilities for landlords and tenant farmers, garnered George Hope an international reputation in agrarian circles.

George Hope, 1811-1876. Agriculturalist.

Painted by Sir George Reid, National Galleries Scotland

George Hope Bertram of Toronto Bay was named for the original George Hope, but eventually promoted an even more ruthless landscape than the Scottish moorlands of his ancestors: the Great Clay Belt of Northern Ontario. In an 1897 brochure addressed to the Attorney General of Ontario, Bertram, along with George Cox and soon-to-be-knighted Sir William Mackenzie, laid out the economic case for a railway line connecting Parry Sound, on Georgian Bay, to the threshold of the mysteries of the Arctic Circle: James Bay. In between those unimaginably distant points were mineral riches beyond description, vast bleak forests, and from the north shore of Lake Timiskaming to Lake Abitibi, a massive stretch of heavy loam soil, deemed suitable for agriculture.

Display of vegetables. “The Great Clay Belt of Northern Ontario”, Teimiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway Commission, 1913. See: https://archive.org/details/greatclaybeltofn00temi/page/n3/mode/2up

Bertram, George Cox and Sir William dreamed big and envisioned pioneer settlement, and in time, the growth of towns and cities, through the establishment of a supportive agricultural and industrial base. (Though their dreams of a ribbon of steel and successful colonization fell flat, the Ontario Northland Railway eventually reached James Bay in 1932. The railway drove the development of the mining boom in the Timmins-Porcupine area and the emergence of Northern Ontario’s pulp and paper industry.)

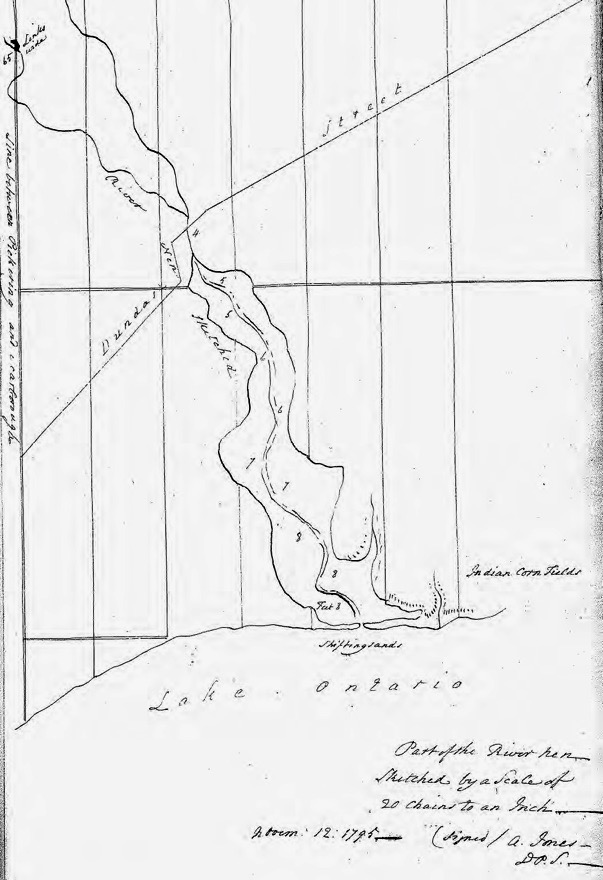

It was through the early years of the James Bay project that Bertram’s son-in-law and my great-grandfather William Henry (Billy) Moore got his start, becoming the Secretary of the Canadian Northern Ontario Railway in 1907. In the midst of the industrial age and by the 1930s a successful Toronto lawyer, economist, author and parliamentarian, Moore also yearned for the land. In 1912 he began the development of his utopian farm, Moorlands, on the outskirts of the city, on the east side of the mouth of the Rouge River, in Pickering Township. (Moorlands is now the Petticoat Creek Conservation Area in the City of Pickering).

Ontario has a long history of agriculture that extends back in time for hundreds of years prior to European settlement. Here is Augustus Jones’s 1795 survey of part of the River Nen (currently known as the Rouge River). Note the presence of “Indian Corn Fields” on the east side of the river, where Moorlands was later developed. Courtesy Archeological Services Inc.

The last of the Moores left the farm in the late 1960s, but in the early 1970s, though then living in a cookie cutter development on the edge of a ravine in southeast Scarborough, we were still driving out to Pickering Township to tend to the land.

. . .

I’m thinking that it must have been about 1972, or very latest, 1973. Our family hadn’t made the move up north, to Brock Township yet, and I was old enough to have a paper route for the Toronto Star in the city. The best part of the gig was the occasional stints I did with Wild Bill, my sweet, inspirational father. My Dad fit his moniker perfectly. Case in point: Wild Bill chucked the afternoon daily out to me through the open window of his moving vehicle, while I stood on the running board, clinging for dear life to the passenger-side door. Was that normal? Probably. Not. But I can tell you that it sure made short work of the route and was a hell of a lot of fun!

It was a race, you see. As soon as we were done, we left the buzz of the city behind us and disappeared up the Altona Road into the countryside, onto lands freshly expropriated for the Pickering Airport. On our minds was land development of a different sort, however. We had potatoes to hoe in what was my parents’ own ‘back-to-the-land’ project: a gigantic garden shared between our family and the families of a few of their forward-thinking friends.

Pickering federal Lands, 2018. For more information on the agricultural potential of the lands expropriated for the Pickering Airport, see: https://landoverlandings.com/.

© Jane Fairburn, 2018.

But at the age of 11 or 12, I wasn’t thinking at all about the issues of food security, organic produce, climate change, or land conservation. I simply adored the moment of being with my Dad in the silence and softening light of the late afternoon. A kind of beautiful decrepitude had already sunk into the land. As we worked side by side down what seemed like endless hills of potatoes, feral ponies gazed at us from untended fences. Multi-coloured tabby and calico kittens tumbled through tall grass. We were happy being together, smelling the earth and tasting a deep sense of belonging to the natural world around us.

Arugula from seed, Meadowcliffe Bluff. © Jane Fairburn, 2020.

My Dad is gone now, and I’ve lived out a large portion of my adult life in the Scarborough Bluffs, on the edge of the lake, a few miles from the curve of Frenchman’s Bay at Moorlands. I’ve always kept a garden in the city. What is it, year after year, that compels me to put my hands back into the earth? Is it the call of my ancestors? Am I trying to replicate those precious moments with my father? Is it a kind of self-administered inoculation against the constant and inevitable change with which each of us grapples?

I do know that working in the earth instills in me a sense of permanence and solidity. It settles me. And there is certitude deep within that though trapped in this linear sense of time, I’ll eventually revert to the clay. You belong here. The affection I feel for the lush remnant forests, fields and nearshore waters of the lake is in my bones. And perhaps that’s why I’m compelled to write about it and grow my garden. To till straight rows and to discover what lies buried, under the earth.

On the Burren, County Clare, Ireland. © Jane Fairburn, 2019.

{ 4 comments… read them below or add one }

Thank you Jane Fairburn. I will read more of the suggested articles and books.

I have always lived in close proximity to Lake Ontario. The love of gardening and growing vegetables was instilled in me by my mother. I have passed this along to our children. The continued plan to cement over the farmlands is as you point out so wrong. We have undone the balance of nature. Hoping for a better plan before it is too late. Lynne Bywater

Thank you, Lynne!

Hello Jane. During the late fifties, as you probably know, Moorlands was home to many immigrants from Britain. Arriving from Birmingham, England, our family lived there for several years, and for my brother and me, it was one of the best times of our lives. We learned to swim, skate and to appreciate the joys of being wild and free, tanned and happy. We knew your grandfather and your great-grandfather, and the beautiful old house he lived in. Your Dad was my grade 7 teacher at Fairport Beach School. Jennifer Ricketts, my friend in Moorlands, arranged for your Mom to be our chaperone on a trip to Niagara Falls with the intention of getting them to fall in love with each other (and here you are!). Your father was without doubt the best teacher I ever knew (although he did try to get me to sit on a sleigh behind his moving car; I guess he never changed!). It was wonderful to learn some of the history behind Moorlands. It was a magical place. Thank you so much.

Hi Linda,

Thank you so much for leaving me your beautiful reminiscences! Moorlands, like, Along the Shore, is a project with many moving parts, and the research has taken place over years, as the book has evolved. I’m off to Concordia University in Montreal this week to gain further insights, and look forward to speaking with you in future, should you be agreeable! All best.